What is changing and unchanging: two years after political change in Japan

CAMPAIGN: SENDING A LETTER TO THE JUSTICE MINISTER

http://www.semisottolaneve.org/ssn/a/35190.html

TO SIGN:

http://www.peacelink.it/campagne/index.php?id=92&id_topic=73

I Political Change and an Unchanged Ministry

1. Expectation for the Justice Minister

On August 30 2009, the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ) won the general election and seized political power for the first time. The following week, the news that Justice Minister Keiko Chiba was appointed attracted much attention from the international community. She was a lawyer-turned politician, who once represented prisoners, and had been known as a member of the Diet Members’ for the Abolition of the Death Penalty, and also as the Secretary-General of the Amnesty Diet Members’ League of Japan.

Prior to the political change, the DPJ had announced its plan to review the death penalty system and consider a moratorium on executions, although public didn’t pay attention to this point[i]. The Minister expressed her will to initiate discussion on the penalty or to disclose the related information accordingly. She also consistently showed her cautious stance on execution. However, nothing was put into action in this regard until July 28th 2010.

[i] http://www.moj.go.jp/content/000057318.pdf

Five months after Chiba took office, the Cabinet Office released the results of an opinion poll about the basic justice system in the country. According to the survey, 85.6% people approved of the death penalty. The responders were given three options from which to choose: “The death penalty should be abolished unconditionally”, “In some cases, the death penalty is inevitable”, “I don’t know/It depends.” Support for the death penalty rose 4.2 points from the previous survey conducted in 2004, while the percentage of abolitionists dropped slightly, from 6.0 % to 5.7 %. Among those who said they approved of the penalty, 54.1% said that the system was needed to satisfy the feelings of the victims and their families, and the percentage rose 3.4 points from 2004. There have been numerous criticisms of the survey method, especially with regard to the fact that there is no option of conditional abolition, for example the introduction of life without parole as an alternative to the death penalty. But it seemed true that more people ‘feel’, not ‘think’ that the death penalty is necessary. Given the figure of 85.6 %, Minister Chiba said that “whether just one survey reflects the whole public opinion or not should be looked into carefully, but the majority sentiment of the public must be fully respected.” Even after this remark, most abolitionists believed that she would not sign any execution warrants.

Another five months passed and Chiba lost her seat in the Upper House election on July 11, 2010. The loss meant that she would never be reappointed as Minister in the approaching reshuffle of the Cabinet. Everyone thought that she had simply failed to take any initiatives to promote public or political discussion, but no one predicted that she would authorize executions, under circumstances where the end of her political career was approaching.

2. Executions by an “Abolitionist” Minister

On July 28th 2010, exactly one year after the last executions took place under the administration of the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), Chiba ordered the executions of two death row prisoners detained in the Tokyo Detention Center. These were the first executions since her inauguration in September 2009, and, at the same time, the first executions which were witnessed by a Justice Minister. One of those executed was a man who withdrew his appeal to the High Court and allowed his sentence to be finalized.

News of the executions surprised people, not only abolitionists but also supporters of the death penalty. “The executions were conducted in a proper way”, she said at the press conference just after the executions. “Watching the executions with my own eyes made me take the issue of the death penalty seriously and I thought that a fundamental debate on the penalty is needed. Now I have decided to set up a Study Panel inside the Ministry of Justice in order to consider the death penalty system.” She also said that she would allow news media to visit the execution chamber, and in late August only limited media representatives were allowed to visit the chamber. However, the hanging rope was not shown to the visitors. Moreover, since then, the Ministry has refused any request to visit the execution chambers, which are located at seven different detention centers.

Thus, under strong pressure from Ministry officials to authorize executions, she merely established an internal review body and allowed a visit to an empty chamber in exchange for the lives of two people.

The Study Panel was aimed at “creating momentum to start nation-wide discussion of the death penalty by publicizing the outcomes of discussion at the Panel”. The Panel had its first meeting on August 6 privately, despite the Minister’s suggestion to have an open discussion. The Panel consists of three DPJ politicians (the Minister, Vice Minister and Parliamentary Secretary of the Ministry of Justice) and ten bureaucrats – seven of whom are prosecutors. The panel planned to discuss the following limited items: 1) the approach to the issue of abolishing or retaining the death penalty system 2) issues related to executions, including giving notice of execution, and 3) providing information on executions, etc.

Chiba said that the Study Panel would invite various people from outside the Ministry and hear their opinions. During the twelve months since its establishment, the Panel has held seven meetings, and a total of 8 individuals or organizations from outside the Ministry were heard on the three occasions. However, it failed to attract attention from not only the general public but also the vast majority of legislators who are busy with politics. In response to establishment of the MOJ Panel, the DPJ created a working group on the death penalty within its judicial division, but the group has not been active so far.

3. Suggestions from Chiba’s failure

Many people outside Japan may have been surprised to hear the story of Chiba. Why didn’t the abolitionist Minister simply order a stay of execution? Doesn’t the Minister have power to implement the policies she wants to?

The answer to these questions is in the following remarks of Minoru Yanagida, Chiba’s successor, who left office only two months after appointment. “When I am asked questions at Diet Sessions, the Justice Minister need use only two sentences: “We cannot answer questions about individual cases”, and “we are acting properly based on law and evidence”. Whenever I don’t know how to reply, I use these sentences. How often I replied that way!” Because of this, he was pushed out from the cabinet, but this episode clearly shows what the ‘expected’ role of a Justice Minister is.

Yanagida’s remarks mean that a person who does not have any expertise in administration of the Ministry’s policies can serve as the Minister. As almost everything is prepared by brilliant bureaucrats, all the Minister has to do is just authorize it. Despite political change, there has been no change in bureaucracy, especially with regard to the Ministry of Justice. The most important reason for this is that the bureaucracy is administered by public prosecutors. Different from other Ministries, which have a two-story system of senior officers and others, the Ministry of Justice has a three-story system: the top level consists of prosecutors-turned officials, senior officials who are not from the prosecutor’s office are below them, and other officials are at the bottom. Political change did not influence this three-tier structure. We can also see how unimportant the Justice Minister is in Japan, as every Minister leaves office after a very short period of time. The longest term is the two years and five months served by Mayumi Moriyama of the LDP.

On the other hand, this strong bureaucracy-led structure means that there has been little room for the Minister to take initiative in order to change the traditional system or practice. Especially with regard to issues which heavily involve the Criminal Bureau, which is occupied by public prosecutors, the Minister has to have both courage and skill to be strong enough to counter political pressure from his or her subordinates. You can easily understand this dynamism when you see the fact that no systematic reforms have been introduced despite a series of recent scandals where public prosecutors have been arrested and indicted (one of them was sentenced to a prison term), because of their fabrications of evidence with a view to convicting innocent people.

Especially, when it comes to the issue of the death penalty, the Justice Minister must be wary of public opinion, which is believed to affect the attitude of voters. Even Satsuki Eda, former Speaker of the House of Councilors, and one of the few politicians who explicitly opposes the death penalty, failed to take any initiative towards abolition or moratorium.

Thus, generally speaking, the role of Justice Minister of Japan has been strictly limited to the authorization of bureaucratic initiatives. This also explains why so much emphasis is placed on the obligation of the Justice Minister to order executions under the Criminal Procedure Law. In other words, the most important task of the Minister is to straightforwardly apply the provisions of the statute book. Therefore, not to sign the execution warrant is regarded as showing an unacceptable ignorance of the law.

4. The Fifth Minister

On September 2nd 2011, Hideo Hiraoka was appointed as the fifth Justice Minister under the DPJ administration. At a press conference on that day, he emphasized that he is not of the view that the death penalty should be abolished. He even said that he did not join the Diet Members’ League for Abolition of the Death Penalty, because he wanted to consider the issue from various perspectives.

Hiraoka, who has experience of working at the Cabinet Legislation Bureau, and possesses an attorney’s license, is quite cautious about the possibility of public opposition to or criticism of his thoughts or decisions on death penalty issues. It seems that not only the fact that Chiba lost her seat in 2010 Upper House election but also his own experience in the 2008 election has caused this cautiousness. In April 2008, Hiraoka was running for the Lower House election to regain a seat in his electoral district, Yamaguchi No.2. The district covers the area including Hikari City, which is well known for the ‘Hikari City Murder Case’, in which a young mother and her 11-month-old daughter were murdered by an 18-years and one-month-old boy. In Japan, a person under the age of 20 is treated as a juvenile, but a juvenile aged 18 and over can be sentenced to death. In 2006, the Supreme Court repealed the original decision of life imprisonment and sent the case back to the Hiroshima High Court. A family member of the victim’s – the young husband – received significant public attention and sympathy, and repeatedly demanded the death penalty for the perpetrator. The High Court decision was expected during Hiraoka’s election campaign. In the middle of the campaign, Hiraoka said that the lives of the victims cannot be recovered by sentencing an offender to death. This comment triggered Hiraoka bashing and he was severely criticized, as if he is an enemy of crime victims. He eventually won the election, but it seems that this experience has made him behave more carefully with regard to the death penalty.

Even so, he seems more active compared to his predecessors. Since the inauguration, he also has shown a very cautious attitude toward executions, and it is understood that he is not willing to order any executions, at least while the MOJ Panel is discussing the issue. Moreover, he reportedly said “now is the time to take action”, which means that national debate on whether to abolish the death penalty should be started[ii]. On the same occasion, he also mentioned the emotions of victim family who demand tougher punishments for offenders, by saying that “to settle a score with offences just brings a spiral of resentment. Instead, measures to support victims must be the focal point.” It is clear that he wants to establish a moratorium on executions and believes that the death penalty should be abolished.

[ii] The plan is expressed in ‘INDEX 2009’, a set of the DPJ’s policies.

II Updates on Japan’s death penalty

Before thinking about our challenges under the new administration, I would like to discuss some recent changes with regard to the death penalty which deserve attention.

1. Facts and Figures

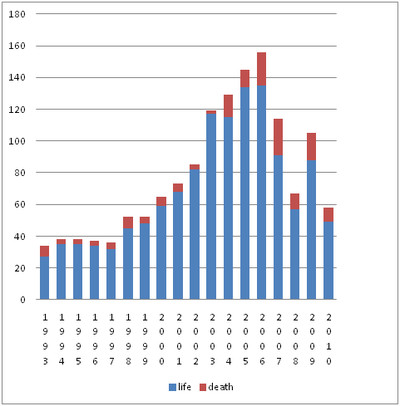

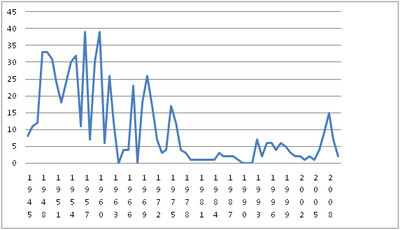

From the year 2000, the number of death sentences began to increase, creating an upsurge in the number of death-row prisoners in the 2000s, which reached 100 in February 2007 for the first time. As of October 21st 2011, it is reportedly said that there are 126 prisoners on death row whose sentences have been confirmed. The expansion of the death row population accelerated the executions, as was clearly shown under the administration of former Justice Minister Kunio Hatoyama, who executed as many as 13 inmates during his 11-month term (Table 1).

On the other hand, the number of homicides, as well as total deaths caused by all offences under the Penal Code, has kept declining and, most notably, in 2009 and 2010, the homicide number was at its lowest level since World War Ⅱ (Table 2).

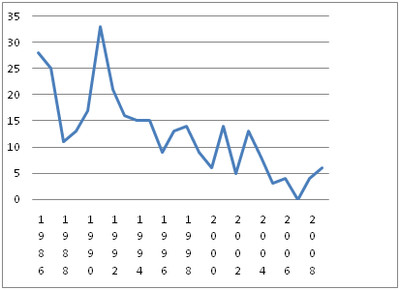

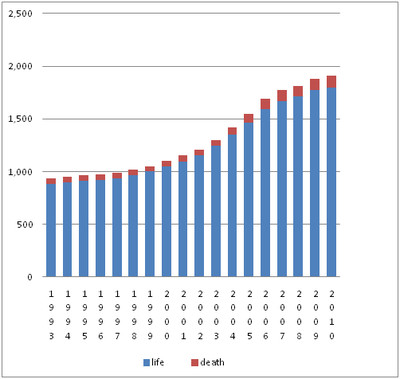

The crucial point here is that a recent increase in death-sentencing is just one aspect of a general tendency to be tougher on offenders. Life imprisonment also dramatically increased in the 2000s. Although a substantial decrease in cases of life imprisonment has been seen in recent years because of the amendment of the Penal Code in 2005, which raised the maximum limit of definite prison term from 20 years to 30 years (Figure 1), the level is still higher than it was during the 1990s. In addition to the volume of sentences, the significance of the punishment today is quite different from the old days: life imprisonment today means that there is almost no possibility of parole. Among nearly 1,800 lifers, only 6 people were released on parole in 2009, 4 in 2008 and none in 2007 (Figure 2). The average period actually served by prisoners before their release is also becoming longer and now it has reached 30 years (Figure 3). Thus, the lifer population has also been expanding (Figure 4). During the decade between 2000 and 2009, 65 lifers were released on parole, while 126 died behind bars[iii].

[iii] http://www.nikkansports.com/general/news/f-gn-tp3-20110917-836616.html.

Figure 1 Prisoners finally sentenced to life, and death

Source: Annual Report on Statistics on Prosecution

Figure 2 Lifers who secured release on parole

Source: Annual Report of Statistics on Probation

Figure 3 Lifers and Death Row Prisoners at Year-end (1993-2009)

Source: Annual Report of Statistics on Correction

2. Lay Judge System

In May 2009, a totally new Lay Judge System was introduced. Criminal offenses that are punishable by death are tried by a court, usually composed of three professional judges and six lay people. Under the system, as of October 21 2011, there have been thirteen trials in which prosecutors sought the death penalty, and eleven of them have already produced verdicts at the first instance. Of these cases, eight resulted in death sentences, two in life imprisonment and one in an acquittal. Although there are various problems with the system, especially from the perspective of capital defense[iv], civil participation has had a substantial impact on both fact-finding and sentencing, especially with regard to capital cases so far.

[iv] See Maiko Tagusari, “Death Penalty in Japan”, East Asian Law Journal, Vol.1, No.2, 2010.

When we survey the capital cases under the new system, there are two key points: the first is that, unlike in the U.S. system, there is no sentencing guideline for courts except for a rather vague standard developed by the Supreme Court, the so-called ‘Nagayama standard’, and the second is that, fundamentally, the stages of fact-finding and sentencing are not separate in Japanese criminal procedure.

According to the Nagayama standard, “the death penalty can be applied only when the criminal’s culpability is extremely grave and the ultimate punishment is unavoidable from the viewpoint of balance between the crime and the punishment as well as that of crime prevention effects, taking into account the circumstances, such as the nature, motive and mode of the crime, especially the remorselessness and cruelty of the means of killing, the seriousness of the consequences, especially the number of victims killed, the feelings of the bereaved, social impacts, the age and previous convictions of the offender, and the circumstances after commitment of the crime.” The lack of a clear guideline means that the sentencing discretion of each court is wide, especially under the Penal Code, which allows a suspended sentence as well as death for a murder. However, until the introduction of the lay judge system, sentencing decisions did not fluctuate greatly, because there was a kind of de-facto standard which had been shared by the professional actors at trials.

Things are quite different today. In cases where defendants admit their guilt, lay judges seem to think and decide more freely, unbound by precedent. The most notable pattern is harsh sanctions for juvenile offenders. On November 25th 2010, a juvenile who was 18 years old at the time of his crime was sentenced to death. Until then, there had only been two cases where death sentences for juveniles had been confirmed since the Nagayama decision, and both defendants were 19 years old at the time of the commission of their crimes. Moreover, when the number of victims killed has not exceeded one, the death sentence has seldom been imposed on a defendant, even if he or she was an adult. However, on June 30, 2011, the Chiba District Court imposed a death sentence on a defendant who murdered one victim, a female university student. The convicted man had set her room on fire and had been charged with several other offences, but had not previously committed murder[v].

Non-separation of the two phases means that if a defendant maintains his or her innocence throughout the procedure, it is almost impossible for him/her to raise the argument that he/she deserves a more lenient sanction than death. The lack of effective activities for mitigation tends to directly lead to the severest punishment when a defendant is found guilty, as was seen in a trial at the Tokyo District Court, where a 60-year-old man was sentenced to death[vi].

[vi] http://www.jiadep.org/Ino_Kazuo.html

On the other hand, lay judges in a Kagoshima District Court case found a defendant not guilty, despite the fact that they believed that the defendant had unlawfully entered the victims’ house. They made a clear distinction between the fact of trespass and the issue of murder, and faithfully observed the rule of ‘proof beyond reasonable doubt’, which could seldom be expected in trials that were only heard by career judges. The ratio of acquittals at lay judge trials is a little higher than that in trials presided over by professional judges[vii].

[vii]To read more about the implementation of the saibin-in system, see: http://www.saibanin.courts.go.jp/topics/pdf/09_12_05-10jissi_jyoukyou/02.pdf

What can we learn from these different tendencies –a very punitive approach to heinous crimes and an attitude strictly observing the basic standard of criminal procedure which could produce an acquittal? I think both of these can be explained by the same reason: for lay people, precedence does not weigh so much, because the case they are considering is the only one they have ever considered, and they will never have similar experience in the future. They are simply concentrating on the case in question, and don’t care about the balance between different cases. Thus, they are not strongly affected by the notion that someone who trespasses into a murder victim’s house is often also the perpetrator of the murder. At the same time, they cannot think that the case in front of them, a really serious offence, is less heinous compared to other capital cases. This also suggests that there is not much room for life imprisonment—and maybe even life imprisonment without any possibility of parole—effectively to work as an alternative to the death penalty, when a defendant was found guilty.

Despite various controversies over the system, however, it is true that its introduction has made people more interested in the matter of how to cope with crimes and the penal system as a whole, including capital punishment.

3. Bills prepared by the Diet Members’ League

For the last few years, the Diet Members’ League for the Abolition of the Death Penalty has been planning to submit a package of bills, which the League calls ‘bills to make the decision of death sentence more prudently’. The package consists of; 1) the introduction of life imprisonment without possibility of parole as an intermediate sanction between the death penalty and life imprisonment with possibility of parole 2) the establishment of a study panel at each house of the Diet to produce research on issues related to the death penalty for a period of three years 3) a stay of executions for four years (the period of research by the study panels plus one year) and 4) the requirement for unanimous agreement in cases where a death sentence verdict is required.

The requirement for unanimity is absolutely necessary, as is a mandatory appeal system for death sentences, and prohibition of a prosecutor’s right to lodge an appeal and seek the death penalty[viii]. The current system only requires a simple majority, which must include at least one career judge and one lay judge. But the unanimous verdict rule seems unlikely to be realized soon, because it requires a revamp not only of the Lay Judge System Act but also the Court Act. Setting up study panels in the Diet is not an easy task too, and a four-year moratorium would also be difficult to achieve.

[viii] See Tagusari, 2010.

Therefore, Shizuka Kamei, President of the League, and leader of the People’s New Party, is hoping that one part of the bill package could be passed: the introduction of life without any possibility of parole. However, an unignorable problem with this attempt to add another severe punishment in addition to the death penalty is that this will not help Hiraoka in his struggle to stay executions.

Apart from the practical problem mentioned above, the idea has a fundamental problem which has been controversial within civil society, because it aims to add another inhumane punishment on top of the death penalty and life imprisonment, both of which types of punishment have dramatically expanded in recent years. Human rights actors including the Japan Federation of Bar Associations have been critical, suggesting that the introduction of life without any possibility of parole might accelerate the recent trend of tougher punishments, which is contrary to the League’s intention to reduce the number of death sentences. This concern is becoming a reality under the circumstances that lay judges tend to choose more severe punishments for serious crimes. Although the League well knows the reality of life imprisonment, they have never tried to confront a trend of ‘penal populism’. Instead of raising public awareness of the realities of the death penalty and de facto life without parole, they believe that a populist approach could lead to a reduction of the death sentences, and ultimately to abolition.

4. A new argument about the cruelty of the execution method in Japan

On October 6 and 7, during a lay judge trial at Osaka District Court, two experts testified about the cruelty of hanging, the only execution method prescribed in the Penal Code of Japan. Strikingly, this execution method has not been changed for nearly 140 years, based on Decree No. 65, issued in 1873, which the Supreme Court confirmed is still valid through its Grand Bench ruling dated July 19, 1961[ix]. Since this decision, which denied the cruelty of hanging, no one has actively challenged the constitutionality of the execution method for the last 50 years. This has been possible because of the government’s ‘secrecy policy’. Almost nothing about the realities of hanging has been disclosed to the public, including how to hang the rope around a prisoner’s neck, which type of rope is used, or the eventual condition of the hanged body. This policy remains active even after Chiba’s decision to allow the media to visit an execution chamber.

[ix] See Tagusari, 2010.

Walter Rable, an Austrian specialist in forensic medicine, testified that it is ‘quite rare’ that prisoners executed by hanging die immediately, and that in most cases, prisoners remain conscious for a while – varying from five seconds to five minutes – and suffer the experience of strangling. Under some conditions, hanging may cause decapitation, either in a complete or in an incomplete way.

Takeshi Tsuchimoto, another expert who has testified to the cruelty of hanging, is a former prosecutor and has experience of executions. Responding to a question from a defense attorney, he argued that the hanging can be said to be “extremely close to cruel”. Then, when asked about the meaning of this reply by a prosecutor, he answered, ‘I hesitated to say so before but in fact I believe hanging is cruel.”

These testimonies are significant but unknown to the public, as well as to ministry officials and the minister. Media coverage was limited, and accordingly the impact of the testimonies has so far been limited. But this is very important information which is highly relevant to general debate about the very nature of the death penalty system itself. Such testimony should definitely not remain confined to individual cases. The verdict is scheduled on October 31th 2011 at Osaka District Court.

5. The JFBA’s new position

On October 6, 2011, the Japan Federation of Bar Associations, to which all Japanese attorneys belong, adopted a new declaration about the death penalty, entitled “Declaration Calling for Establishment of Measures for Rehabilitation of Convicted Persons and Cross-Society Discussion on Abolition of the Death Penalty”[x]. Until then, the JFBA had supported a moratorium on executions mainly on the grounds that Japan’s death penalty system has numerous flaws, but had never explicitly supported abolition. However, the JFBA has now stated that it is in favor of abolition, and declared that “regarding the death penalty, which completely closes the door to the possibility of the rehabilitation of convicted persons, cross-society discussion on the abolition should immediately be commenced, and executions should be suspended while the issue is being discussed.” It also requires disclosure of necessary information and reform of the system while discussions are held. The notable point is that the JFBA has raised the issue of the death penalty as a matter of how society should approach crime. It is expected that the JFBA will play a more active role, in an effort to implement a moratorium, with a view to abolishing the death penalty.

[x] Full text is available at: http://www.nichibenren.or.jp/en/document/statements/year/2011/20111007_sengen.html6. Miscarriage of justice

As seen in the Illinois case, an example of a miscarriage of justice should offer a useful pretext for starting discussions on abolition. However, Japan is such a unique country that miscarriages of justice have never led to systematic reform. It is well known that in the 1980s four death row inmates were exonerated after they had been found not guilty at retrials[xi]. And yet nothing changed in the criminal justice system.

[xi] Menda case in 1983, Saitagawa case in 1984, Matsuyama case in 1984, and Shimada case in 1989.

In March 2010, a man named Toshikazu Sugaya, who had been wrongly sentenced to life imprisonment, and had actually spent 17 years in detention based on a false confession and the totally erroneous result of a DNA test, was exonerated after his acquittal at retrial. He had been forced to confess to another two murders in addition to the one of which he was actually accused; thus, he could have been sentenced to death.

In June 2011 another two men, Shoji Sakurai and Takao Sugiyama, who had been sentenced to life for a robbery and murder case in 1967, were acquitted at retrial. They were also forced to confess to a crime which they did not commit. And at the time of writing, another prisoner serving a lifetime prison term is waiting for a decision on whether to reopen a case where a woman was robbed and murdered in 1997. He maintained his innocence throughout the criminal procedure and was acquitted in the first instance, but was found guilty by High Court judges who ignored the importance of objective evidence.

All these cases have come to light because they were lifers and are all alive. Although the Legislative Council of the Ministry of Justice has just started discussions on possible reform with regard to criminal justice matters, a series of serious miscarriages of justice don’t seem to have precipitated a drastic review of the criminal justice system. This is because of a strong campaign by the bureaucracy and its partners, a group of academics who can always be relied on to support the Ministry.

Even so, we must continue our efforts to link wrongful conviction cases to reform of the system. By the end of this year, 2011, it is expected that the Supreme Court will make a decision on a retrial request regarding the Nabari Case[xii]. This is one of the most well-known capital cases, in which the convicted person is widely believed to be innocent, along with the Hakamada Case[xiii]. If the decision is positive, it would also help the Minister to take stronger initiatives towards a moratorium.

[xii] International Federation for Human Rights (fidh) “The Death Penalty in Japan: The Law of Silence” pp. 24. http://www2.ohchr.org/english/bodies/hrc/docs/ngos/FIDHJapan94.pdf

[xiii] See Amnesty International “Japan: Hanging by a thread: Mental health and the death penalty in Japan”, pp.38-45

III Challenges for Abolition

1. 2011: An Epoch-Making Year?

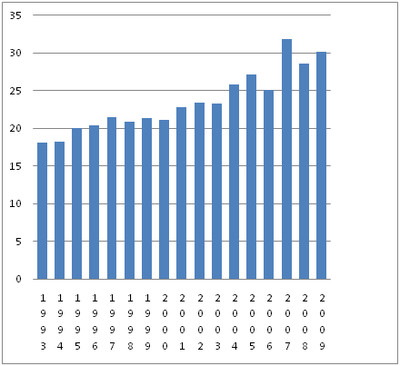

Since the last execution ordered by Chiba, there has been no execution for 15 months at the time of writing. As of October 2011, there are 126 prisoners on death row whose sentences have become final. This number is a record and some sections of the media argue vociferously that executions should resume in accordance with the law. There are only two months left before the end of the year. If there are no executions in 2011, this would be the first execution-free year since 1993 (Figure 4).

Figure 5. Annual Executions (1945-2010)

Source: Annual Report of Statistics on Correction

To have a year without an execution is crucial to the achievement of a de facto moratorium. The bureaucracy is of course keenly aware of recent execution history. MOJ officials have done their best not to have an execution-free year for the last two decades. If we can avoid executions for the remainder of the year, however, MOJ officials will have a new precedent of which they would have to take careful note.

2. Hiraoka’s challenge and the role of civil society

On the other hand, it is true that, with the end of the year close at hand, Minister Hiraoka is facing more pressure from bureaucrats who adhere to retention of the death penalty. Hiraoka said “some people say not signing off executions is sabotaging the duty of the justice minister, but the minister also has the duty to consider how to handle the death sentence amid various international opinions on the subject[xiv].” It seems that he definitely wants to make a step towards, at least, a moratorium, despite the pressure from the bureaucracy.

[xiv] Minoru Matsutani “Hiraoka urges ‘active’ debate on executions”, The Japan Times, September 20, 2011

On October 17, 2011, at the 8th meeting of the MOJ’s Study Panel, which was the first one attended by the new minister, Hiraoka, he made the following observation:

Since the establishment of this Panel, two meetings were held under Chiba, one under Sengoku and three under Eda. Every Minister said that he or she expected that this Panel would trigger national debate on the issue of the death penalty. However, it seems that national debate has not been started yet so far. I hope that Japanese citizens will have discussions on this issue, and become fully informed about the international trend or unique position of Japan as one of the developed countries in this regard, in a way that the Japanese people’s argument would be understood and regarded, by the international community, as that of a developed country. In order to have a real ‘national debate’, we need to sincerely consider how to handle this Panel and what other opportunities we should have. I beg your understanding and cooperation.

To start this ‘national debate’ on abolition, Hiraoka is seeking to set up a totally new forum, which would also continue to provide him with a ‘compelling reason’ for not signing off on executions.

The most feasible option for Hiraoka would be to establish a special panel on the death penalty, which is not an internal body of the ministry, but which would be composed of various stakeholders from outside the ministry and completely open to the public, with a mission to conduct thorough research and debate based on facts and figures drawn from around the world. It is fundamentally important that this panel must challenge the existing system, and not be a mechanism through which to justify the old framework and old practices.

As I have discussed above, there are a number of problems in Japan that relate to the issue of the death penalty, for example the cruelty of execution, miscarriages of justice and problems surrounding capital trials. The issue of the death penalty, which reflects the society in which we live, should be raised in connection with many other social matters, although it has often been addressed separately from other issues in the past. It is important and necessary to effectively compile all necessary information relating to the death penalty, and present it as a package which requires real debate, and which can help generate momentum towards abolition. For this purpose, a cooperative network of civil society actors, which has until now been relatively weak in Japan, mainly because more energy has been put into support of individual cases, must be strengthened. In this regard, the JFBA, which has just expressed its determination to support abolition, would be in a good position to take the initiative.

At the same time we should not forget another important lesson from Chiba’s failure: never allow the Minister to become isolated. Surrounded by strong supporters of the death penalty day and night, the Minister tends to become isolated and think in a negative way about the difficulties he or she is facing. Actors such as Bar Associations and other human rights organizations have to be beside the Minister, providing important information and conveying strong support from various fields, in order that the Minister will not give in to pressure, and will instead continue to defend, sustain and promote the case for abolition.

Excurses

On top of the bureaucracy, now Hiraoka is facing the pressure from the DPJ-led Cabinet. On October 26 2011, Chief Cabinet Secretary Osamu Fujimura said at Diet session as follows: “the Cabinet has no plan to abolish the death penalty and it is the role of Justice Minister to sign off eventually after reflection. I’d like to say to Hiraoka that he should clearly express his own opinion (on the role of Minister)”. It seems that Fujimura does not know anything about ‘INDEX 2009, in which the DPJ declares its position to review the death penalty system. After that, Fujimura had a meeting with Hiraoka, and on October 28, Hiraoka announced at a press conference that he will examine each finalized capital case separately from the discussion at the MOJ Study Panel, which suggests a possibility of execution by the end of 2011.

[[Img16363]]

Allegati

- Aggiornamenti sulla pena di morte in Giappone (testo inglese) (280 Kb - Formato pdf)Avv. Maiko Tagusari - Fonte: autricerelazione presentata in ottobre 2011Copyright © Avv. Maiko Tagusari

Tutti i diritti riservati

Il documento è in formato PDF, un formato universale: può essere letto da ogni computer con il lettore gratuito "Acrobat Reader". Per salvare il documento cliccare sul link del titolo con il tasto destro del mouse e selezionare il comando "Salva oggetto con nome" (PC), oppure cliccare tenendo premuto Ctrl + tasto Mela e scegliere "Salva collegamento come" (Mac).

Il documento è in formato PDF, un formato universale: può essere letto da ogni computer con il lettore gratuito "Acrobat Reader". Per salvare il documento cliccare sul link del titolo con il tasto destro del mouse e selezionare il comando "Salva oggetto con nome" (PC), oppure cliccare tenendo premuto Ctrl + tasto Mela e scegliere "Salva collegamento come" (Mac).