Fukushima must not repeat past mistakes

28 gennaio 2013 - Yukari Saito (translated by Gerry Blaylock)

Fonte: Centro di documentazione Semi sotto la neve - 28 gennaio 2013

Know your adversary

1 Do not take responsibility. Use sectionalism to pin blame on others.

2 Confuse victims and public opinion, creating the impression that there are pros and cons on each side.

3 Position victims in conflict with each other.

4 Do not record data or leave evidence.

5 Stall for time. 1

These are some of the strategies adopted by the Japanese authorities against the victims of the Fukushima nuclear accident.

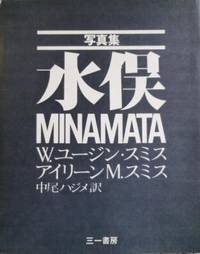

The list was compiled by Aileen Mioko Smith, founder and head of 'Green Action', a not-for-profit NGO based in Kyoto that has been active against nuclear power for more than twenty years. According to Aileen, they are identical to the methods used in the past against people struck by the Minamata syndrome, acute mercury poisoning, brought about by industrial waste dumped into the sea. The first cases were recognised in 1956. Who better than she could describe the mechanism of development which is wearing down the victims? She was born in Tokyo in 1950 of an American father and Japanese mother. As a very young woman she worked alongside Eugene Smith, the legendary American photographer, who later became her husband. They went to live in Minamata on the southern island of Kyushu from where they denounced to the whole world not only the illness but also the industrial crimes and the afflictions suffered by the victims.

The list continues:

6 Conduct tests or surveys that will produce underestimated results on damage.

7 Wear victims down until they give up.

8 Create an official certification system that narrows down victim numbers.

9 Do not release information abroad.

10 Call on academic flunkies to hold international conferences.

After reading the last point, we can't refrain from exclaiming bitterly, 'Dead right!' Because from 15-17 December 2012 a ministerial conference organised by the Japanese government and the IAEA (International Atomic Energy Agency) was held in Kōriyama in the Fukushima prefecture. The meeting, with guests from 117 countries and 13 international organisations, produced what civil society feared: a self-satisfied document which minimised the current situation without any attention paid to the real needs of the people who are paying the consequences of the disaster.

'Even though Fukushima has taught us how we need to separate the government safety regulatory body from the one that promotes nuclear energy, the Japanese government has gone back to its old tricks: to play down the disaster, it has resorted to the IAEA's international authority, which is a mix of both', comments Mrs. Smith.

Divide and rule

'Still in Fukushima?' The kids, too?' 'How can you stay there, why don't you leave?'

These are the questions that many people, who for one reason or another have stayed in the prefecture, find wearing when they hear them. The questions deepen their guilt feelings, especially as regards their children. Through hearing those words repeatedly, they end up forgetting to put a mask on, forgetting to pay attention to the radiation levels, to think about it all – in other words they pretend nothing is wrong, out of a need for psychological survival, more than anything. Arguments are sparked off between victims, family members, old friends. Even if they don't actually have heated arguments, between those who have stayed and those who have left distances have grown, there is reticence and incomprehension between people that lived side by side in harmony before the accident.

Anyone who imagines that the people who left the prefecture to save their children from radiation were quite well-off are mistaken: most of them were single mothers who had nothing to lose by going away. With no home of their own, no steady, well-paid job, let alone family members or relatives etc., they were free from ties and restraints of various sorts.

Meanwhile, central government and local administrations were inviting the inhabitants to start over again by playing on their love for Fukushima. They announced that all financial aid for those who wanted to leave the prefecture would be suspended, maintaining that the alarm had ceased to exist for may areas thanks to decontamination measures. This was the context in which the IAEA gave their approval to the Japanese government.

Notwithstanding this, the latest surveys by a local newspaper show that three out of four inhabitants would like to see the immediate demolition of all six nuclear reactors still present in the territory (apart from the four reactors involved in the accident which are already being demolished).

However, the survey's data, which seems entirely reasonable, is in contrast with the policy of the new government which took office a few weeks ago. Various ministers in Mr. Abe's government have already made known that they want to start up nuclear business again and put aside the plan to stop relying on nuclear energy by 2039, which was agreed last autumn after very lengthy discussions.

This u-turn was welcomed heartily by Mr. Nishikawa, the governor of another prefecture, Fukui, which has all of 14 reactors in a coastal area of less than 60 kilometres. At the first press conference of the new year, he repeated his request to reactivate as soon as possible those reactors which have been shut down for tests, and to start the construction of new ones, also criticising the geological inspections that are taking place to verify whether new, active fault lines exist below some of the reactors, which could lead to their being demolished.

This u-turn was welcomed heartily by Mr. Nishikawa, the governor of another prefecture, Fukui, which has all of 14 reactors in a coastal area of less than 60 kilometres. At the first press conference of the new year, he repeated his request to reactivate as soon as possible those reactors which have been shut down for tests, and to start the construction of new ones, also criticising the geological inspections that are taking place to verify whether new, active fault lines exist below some of the reactors, which could lead to their being demolished.

Fukui is a nuclear trap

How come the prefecture of Fukui insists so much regardless of Fukushima? To understand the motives a visit to the area could be useful. The prefecture, with its 800,000 inhabitants in slightly more than 4000 km2 is 500 kilometres from the Fukushima Daiichi plant, and on the Sea of Japan, which separates it from the Korean peninsula. It lies to the north of the ancient capital of Kyoto.

I visited the area in the company of two men: Mr. Naomi Toyoda and Mr. Masaru Ishichi. Mr. Toyoda is a photojournalist resident in Tokyo and author of several books on Fukushima and wars in the Middle-East. He is also an expert on depleted uranium. Mr. Masaru Ishichi is a local activist (Wakasa Association of Concerned Residents about Plutonium-thermal Power) in his sixties who drove us around.

A dark, freezing day towards the end of December with gusts of sleet. Every so often a small crack appeared in the clouds and we could see the blue sky winking at us. 'The weather's always like this in winter,' says Masaru, as though he had read our thoughts about choosing the wrong day.

The first stop is the Tsuruga Visitor Center, a museum incorporated into the nuclear plant complex with its three reactors, one of which is in the process of being demolished. The museum, which receives a lot of visits by school children, offers a large quantity of reassuring information and fun games, apart from a panoramic view of the plant itself, which looks very modern and aseptic, having been recently repainted. In reality no. 1 reactor is forty-three years old and among the oldest still producing. Its demolition, which should have taken place in 2009, was put off due to delays in building new reactors.

In the meantime, some researchers have revealed their strong suspicion that the numerous fault lines below the plant are active, making its future uncertain.

'Since the plant was idled after the accident at Fukushima, the city's been in deep crisis because all the local economy revolves around the plant,' explains Masaru. 'There's nothing worse than this uncertainty, not knowing whether they'll be reactivated or demolished.'

Why can't they decide to demolish them? It would create good opportunities for employment for the next few decades, which would give them time to develop an alternative economy.

'On an abstract level they understand this, but they can't begin to imagine it concretely because there isn't a detailed road map,' replies Masaru. Then he tells us the story of how this plant was built – the first in the area, a milestone. 'You need to realise that this was an area completely abandoned by administrations before. The inhabitants accepted the first nuclear plant in exchange for a tarmac road.'

We are driving along the two-lane state highway 27 which has pipes at guard rail height on the curves and at the traffic lights from which antifreeze is automatically sprayed. Should an emergency happen, like the one at Fukushima, all the people will take to this road, still the only main road they have.

'The electricity companies: The Japan Atomic Power Company and The Kansai Electric Power Company, knew how to weaken the people's spirit: they provided workers and cash for local fairs, they invited girls from the villages to dinner with young employees. With these and other crafty ploys the companies managed to neutralise the local community and make those in opposition, or who were wary, the minority, where before both positions were widespread.'

Once the first plant had been built, the surrounding municipalities began to become interested in having new ones, attracted as they were by the prosperity Tsuruga enjoyed and also thanks to the huge pro-nuclear incentives offered by the government, which became the main resources for the local authorities' budget.

'Not that the wariness towards nuclear energy has vanished,' explains Masaru, who has always lived in the area, 'Far from it! People, resigned to the situation, said "Well, we'd have happily done without nuclear energy if we'd had a goldmine here. The fact is there's nothing apart from fishing."'

So other plants sprang up one after the other. In the 1970s three reactors at Mihama, in the picturesque bay west of Tsuruga, followed by the Takahama plant further west of Mihama, with four units built between 1979 and 1993; then the famous four in Ooi between Mihama and Takahama; finally, at the start of the 90s, the well-known Monju fast-breeder reactor, in a small, lovely bay on the opposite side to Tsuruga on the same small peninsula, in a hamlet of 15 families reached by dirt roads.

'The decision taken by the inhabitants to accept the latter was not reached without great difficulty, but in the end they said, "we're already surrounded by plants and exposed to risk, what's the point, then, in resisting and doing without all the benefits?"' After listening to the story, the anti-nuclear photographer, Naomi Toyoda, nodded and muttered, "Sure. I understand. In their place I'd have certainly done the same."'

A road without a nuclear plant: Obama

Only the municipality of Obama, situated between Ooi and Mihama – an ancient port which was an open door to the Korean peninsula for the capital, Kyoto, in mediaeval times – has resisted the temptation and refused offers several times. How have they managed?

'The local fishermen were split in two: one cooperative for, the other against,' our driver recalls. 'I'm talking about the seventies, a time when all the municipalities in the area were being constantly wooed by electric companies. The leader of the cooperative against the plant went to speak with the conservative member of parliament and asked him whether he would like to have a nuclear plant in front of his house. To the man's negative reply, the leader told him that the inhabitants were willing to do without a nuclear plant if the politician could guarantee them a good tarmac road. Successively, elections for the mayor took place, with petitions promoted by both sides, which gave the inhabitants the opportunity to express themselves: the vote went firmly against building a plant with something like 13-14,000 against and 3-4000 for. Also last year just before the re-activation of the Ooi plant, the town council approved unanimously an appeal to the national government to draw back from its dependence on nuclear energy.'

While we were driving along the road, with banks of snow piled up on each side, the car radio switched on at low volume broadcast news on the subject: 'The day after tomorrow, geological investigations below the Ooi plant will start up again. 2012 began for us with the news about stress tests for the plant given the urgency to start it up again to avoid a summer blackout ... We end the year with news that could decide the fate of the plant...'

Doesn't what has happened at Fukushima frighten Fukui? According to Masaru, the Governor of Fukui, Mr. Nishikawa, at any rate, does not see it as a serious, immediate threat despite great perplexity repeatedly expressed by the Governors of the bordering prefectures of Shiga and Kyoto. Mr. Nishikawa's position on this point is different from that of his counterpart in the Niigata prefecture which has eight TEPCO reactors at Kashiwazaki-Kariwa. After the large earthquake in Niigata in 2007, which revealed the plant's fragility, the Governor's attitude has become more cautious. Furthermore, the inhabitants have recently promoted a popular referendum to express themselves on the future rapport of their prefecture with nuclear energy.

'That doesn't mean the inhabitants of the Fukui Prefecture share the Governor's view,' points out Masaru, 'even those who live here and are not opposed to nuclear energy feel that such a high concentration of reactors in our territory is unjustified. Deep down we know that we can't continue with radioactive waste and spent fuel, which are filling up the storage facilities. Sooner or later we'll be forced to face that problem.'

As a matter of fact, even the director of the Tsuruga Museum who took us round on our visit confided that after Fukushima he could not believe in technological perfection since it is a human creation which cannot guarantee 100% safety. (Yet as regards nuclear waste he was counting on future technology to be able to come up with a solution to make their radiation harmless.)

In reality, not even the Governor of Fukui is attached to the nuclear project for nuclear energy itself. What he is attached to is the money. In the year 2010, of around 188 million euros for incentives to local authorities who house nuclear plants, the Prefecture collects over 40%, which rises to 60% of the total sum over the last 24 years. In other words, roads, services and jobs in administration are paid through having the atom on your doorstep.

A missing link: Imagination.

Of the four nuclear sites we visited, the one that sticks in my mind the most was the facility at Ooi. After leaving the centre of Obama and driving for fifteen minutes along the tortuous coastline, the car stopped at the bottom of a narrow road which ended at a tiny breakwater. Surrounded by small, dark promontories, it seemed we were on the bank of a lake in the middle of the mountains. Fog was coming down and it had already started to get dark. Suddenly we realised there were two grey drum-shaped buildings half-hidden between the promontories in front of us, emerging from the fog. Looking through his camera lens, Naomi exclaimed, 'Aha! We've caught you. I see they felt the need to hide you.'

In 2012, while I was following the debate regarding the reactivation of units 3 and 4 of this utility, I often heard protests by the people of Obama who requested to have a say in the matter because they were exposed to risk much more than the inhabitants in the Ooi municipality. Now, after seeing the place, I feel their terror very keenly.

Taking us back to the railway station, Masaru asked us for advice on how to make the local opposition to nuclear plants stronger and more efficient. Despite numerous difficulties, he believes it is possible to change the situation because for years he has been talking with the local supporters of nuclear energy and says almost nobody shuts the door in his face and he always manages to find quite a few feelings and opinions in common. 'People avoid talking about it in the family and at work out of fear of arguing, but with strangers it is easier and they can say what they like. Talking about it is important.'

The photographer's suggestion was to suggest the administration simulate an evacuation over a thirty-kilometre radius. On the strength of his visits to zones hit by earthquakes and to Fukushima since March 2011, Naomi explains it to him: 'Participation must be compulsory. Everyone: the elderly and babies, the sick and disabled must be moved over a short period of time. Can we do it? Maybe instructions can be given on how to take potassium iodide to protect the thyroid. The radio can announce: "Dear motorists, if you have your pills with you, it's time to take them." Someone will say, "Oh, damn, I left them at home!"' he says, almost amused at the thought. 'Anyway, it will serve everybody to realise how much the infrastructure works or fails to work – "if an accident took place on state route 27, how could we flee?" – and it will highlight how impossible it is to protect everyone. At the end, tell them they will not be able to go back home for years! A lot of them will be convinced that nuclear money is not worth your life.'

The power of memory: how to connect the past, present and future

Fukushima e Fukui: two similar yet distant realities: the first puts before us real, current problems to solve straight away, the second shows us a still sleepy future that urgently needs to learn from others' experiences before it's too late.

I recall the comparison between the story of Minamata and the ups and downs in Fukushima. And Aileen Mioko Smith is not the only one to point out to us the similarities between the two experiences.

'I don't recognise any substantial difference between the cases of industrial and nuclear pollution,' Mr. Chuko Kondo, a lawyer, declares. At the start of the 1970s he was head of a defence team for the victims of a case similar to Minamata, the Itai-itai sickness, which erupted in Toyama, in central Japan. This was the first case to win a victory in court in the long history of defeats the victims of industrial pollution in various parts of the country suffered. Today, at eighty years of age, Mr. Kondo is dedicating his time to two trials against the nuclear industry: one in Fukushima to defend the evacuees' rights, the other in Kyoto to idle the Ooi plant, hoping his experiences might serve to open up a new era of victories even in the history of trials related to the nuclear industry, which so far have racked up only defeats.

'The methods used by those who have caused pollution are always the same; our difficulties, too. If our Itai-itai case had some strokes of luck – the media on our side, the victims compact and the humanity of the judges, which we able to bring out – the battle for the Minamata victims was much longer and tormented.'

The fact that similar difficulties are mounting in Fukushima almost 22 months after the disaster worries Aileen and many others a lot. What is needed is to help the victims with our creating further lacerations in families, school, at work and in the social tissue. 'Those with Minamata disease have suffered, and still suffer after 50 years,' Aileen reminds us. We have to avoid Fukushima producing a similar tragedy without end.

1Fresh Currents, ed. Eric Johnston, Kyoto Journal - Heian-Kyo Media, 3rd edition, Kyoto, Japan, October 2012, p. 91

Copyright © Yukari Saito

Tutti i diritti riservati